|

|

The informal economy and its impact on tax

revenues and economic growth. The case of Peru,

Latin America and OECD countries (1995 – 2016)

|

|

Guillermo Boitano

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú

gboitano@pucp.pe

Deyvi Franco Abanto

Universidad de Lima

deyviabanto@gmail.com

https://doi.org/10.18800/360gestion.201901.005

|

|

|

El objetivo principal de la investigación es determinar el tamaño de la economía

informal en Perú, América Latina y los países de la OECD, así como estimar el

impacto de la economía informal en la recaudación tributaria y el crecimiento

económico. Para alcanzar el objetivo, la aproximación se realiza a través de

modelos MIMIC. Los resultados principales muestran que el tamaño promedio de

la economía informal como porcentaje del PBI en el Perú es 37.4%, en los países

de América Latina es de 34%, y de 19.83% para los países de la OECD; es decir, un

poco menos de la mitad del promedio de América Latina.

Palabras clave: economía informal, gestión estratégica, crecimiento económico, impuestos, América Latina

The main goal of the research will be to determine the size of the informal economy in

Peru, Latin America and OCDE countries as well as to estimate the impact of the informal

economy on tax revenues and the economic growth. To achieve the goal, the approach

is made through MIMIC (multiple-indicator and multiple-cause) model. The main results

show that the estimated average size of the informal economy as a percentage of the

GDP in Peru is 37.4%, in Latin America is 34%, and in OCDE countries is 19.83%, which

represents less than half of the Latin America average.

Keywords: informal economy, strategic management, economic growth, taxation, Latin America

|

|

|

|

|

1. Introducción

For the last 20 years, Peruvian economy has maintained a sustained growth of 5%, unlike

Latin America (3.8%) and OECD (2.7%). It has been one of the few economies to overcome

the 2008 crisis with a GDP growth. Accordingly, Peru's tax revenues (17% in 2015) have

also grown during the last 20 years, but not at the same magnitude as the OECD (35%) and

Latin American countries (22%) (OECD, 2016). However, in spite of being one of the most

solid economies in Latin America, there is a complex phenomenon: the informal economy,

with negative impact on both the economy and society. For the purpose of this paper, we

will use the definition of informal economy proposed not only by De Soto (1986), who

understands this phenomenon as a source of entrepreneurship that seeks income outside

the formal economy due to the pressures of government`s regulation, as well as the one

proposed by Buehn, Dell’Anno, and Schneider (2012), Schneider and Colin (2013), and INEI

(2016), that describes the informal economy as the set of productive activities subject to tax

and social contributions, consciously hidden from the tax authorities due to tax burdens.

Besides, in this paper, the theoretical concepts will be based on what was developed by

Voicu (2012).

Reducing informal economy is fundamental not only for tax collection purposes

–as tax base could be increased and tax evasion reduced–, but also for Peru’s economic

growth. However, focusing only in tax purposes, the tax structure in Peru and Latin

America is dominated by indirect taxes, which results in low redistributive capacity and

higher inequality. On the contrary, in OECD countries, the system is progressive meaning

concentrated in direct taxes. Concentrating on direct taxes improves welfare and equality

but is only possible by absorbing the informal economy and reducing informal employment

(OECD, ECLAC, CIAT & IDB, 2016).

Most of the phenomenon is analyzed from the economic perspective, even though

informal economy is also relevant within the management area. For instance, Godfrey (2011)

and Mc Gahan (2012) agreed that the informal economy is a «new frontier for management

scholarship and research (Godfrey, 2012, p. 233)» because these businesses structures

work in an environment where management theories could be stressed. Informality does

not imply the business does not look for returns, lack of strategies and avoids competition

and an ethical dilemma (Godfrey, 2011). Not including these activities in the management

analysis and research is to look at half of the picture (Mc Gahan, 2012). Complementing the

idea, Bruton, Ireland and Ketchen (2012) added that although the informal economy is an

important topic due to its great participation in the economy (especially the emerging ones)

there is little research about it and many possibilities to increase the knowledge on the topic

when expanding the areas of study beyond the features and character of the informality.

Bruton, Ireland, and Ketchen (2012) indicated that «the informal economy is the final frontier

of the management domain (p. 2)». Additionally, Welter, Smallbone, and Pobol (2015)

indicated that the informal sector is associated with the informal entrepreneurship that

offers empowerment, emancipation and participation to activity. The entrepreneurial spirit,

then, can empower people in a similar way to the first discussion on the duality between

the informal and formal economy (Welter, Smallbone & Pobol, 2015). Moreover, Darbi and

Knott (2016) described the SNP (Strategic Networking Practices) between companies in an

Guillermo Boitano & Deyvi Franco Abanto

130

informal economy around four interconnected topics: 1) open communication, 2) fraternal

substitution, 3) commitment, and 4) naturalization. It shows the degree to which tacticians

can bring non-economic and «non-rational» personal and social considerations to the

strategic decisions they make on behalf of the organization; thus, the total comprehension

of the strategic methods of informal businesses is improbable without considering these

types of stimuli (Darbi & Knott, 2016). These findings contribute to profound awareness of

the social linkage perspective on strategic networks, and to the use of SAP (strategy as

a practice) in strategic activities, options and practices aimed at individual professionals

immerse into a social environment (Darbi & Knott, 2016). After proposing four possible policy

options. Besides Williams (2015) showed that, if nothing is done, the existing undesirable

effects on formal entrepreneurs, informal entrepreneurs, customers, and governments

will remain. There is no evidence that formal sector deregulation addresses informal

entrepreneurship, whereas the eradication of informal entrepreneurship would result in

governments suppressing and destroying the entrepreneurial effort and the corporate

culture they actually try to foment; thus, the transformation of informal entrepreneurship

into a formal one is shown as the most possible political alternative (Williams, 2015). The

current method in which direct limits are used to enhance detection and escalate penalties

is still quite perfectible as there is a much broader set of tools – not mutually exclusive–

available to address informal entrepreneurship (Williams, 2015). Mukherjee (2016) indicated

that the informal economy is huge and will persist in time. Indeed, depending on how it is

defined, it could be the most dominant model of economic organization and therefore calls

for an appropriate policy response that can promote equitable linkages between formal

and informal economies. It rejected the idea that informal firms act as a weak substitute

for formal firms (Mukherjee, 2016). Finally, Mathias, Lux, Crook, Autry, and Zaretzki (2015)

pointed out that while property and social policies serve to permit formal activity and

decrease informal activity, structural and financial policies limit formal activity and rise

informal activity.

In sum, the main goal of this research will be to determine the size of the informal

economy in Latin America and OCDE countries to estimate its impact on tax revenues and

the economic growth, and to analyze the structural changes needed to increase formality.

Especially attention will be paid in the case of Peru, trying to elaborate recommendation

to better understand its informal economy and how to integrate it into the national formal

economy.

2. Definition of informal economy

An open definition rather than a concrete and closed one is needed due to three reasons:

1) a singular and arbitrary definition could leave out many characteristics and not reflex

the current phenomenology, 2) a precise definition could end up with an inadequate

mechanism of measurement, and 3) different countries have informal economies with

different characteristics (Eilat & Zinnes, 2000). Bovi and Dell’Anno (2009) recognized that

the shadow economy has not a unique and agreed definition, nor does it have a common

name.

Smith (1987) defined the informal economy as a non-formal one that does not

consider in the national accounts. Ogunc, Fethi, Yilmaz, and Gokhan (2000) mentioned

that a «parallel» or «shadow» economy are terms used to refer to it although no formal

agreement exists about a definition. Schnider (1986), cited by Ogunc et. al. (2000), defined

the informal economy as the set of activities that add value and could be accounted

for the national income but are not registered. Smith (1994), as cited by Ogunc et. al.

(2000), considered the production of goods and services that are not included in the GDP.

Bagachaw (1995), cited by Ogunc et. al. (2000), points that it should be divided into three

categories: 1) the informal sector, 2) the parallel markets, and 3) the black markets. Eilat and

Zinnes (2000) mentioned that the term «informal» has been mainly used to refer to small

and artisan activities usually carried out in developing countries. Other terms recognized

by Eilat and Zinnes (2000) are «hidden» and «underground» economy, used to refer to tax

avoidance; the «parallel» and «black» economy, refer to illicit activities; the «unofficial»

and «unrecorded» economy refer to non-recorded activities in the national statistics; and

«shadow» economy (following Tanzi (1982)) points out activities in which the government

has not intervened or endorses.

Frey and Schneider (2001) recognized terms such as «informal», «unofficial»,

«irregular», «parallel», «second», «underground», «subterranean», «hidden», «invisible»,

«unrecorded», «shadow», «moonlight», and «black». There is not a unique definition and

all of them depend on the objective of the analysis. Thus, the normal way of treating the

informal economy is relating it to an unrecorded activity in the GDP. However, under this

assumption, activities such as household activities and tax avoidance are not included in

the statistics because they are not value-added activities (Frey & Schneider, 2001). Finally,

Frey and Schneider (2001) specified that the informal economy cannot be confused with

illegality (activities against the Law such as drug distribution, for instance (p. 7442)).

According to Gylys (2005) there are several terms used for defining the informal

economy, most of which are related to negative aspects of the phenomenon. What matters

more is the fact that the attention is set more in the name than in the fundamentals of the

economic phenomenon (Gylys, 2005). Hence, in the economic life, there are five different

aspects to consider: 1) the official or regulated economy, 2) the unofficial or unregulated

economy, 3) activities not fulfilling with official requirements, 4) registered activities, and 5)

unregistered activities. The first three are linked to formality of the economic activity while

the last two relate to the possibility of registration of the activity (Gylys, 2005).

According to Brambila and Cazzavillan (2010), the terminology «informal economy»

was first used by Hart (1973; 1990) to explain the characteristics of the labor market in

Africa. In addition, Brambila and Cazzavillan (2010) also mentioned all the different ways to

measure it. This definition is used by the International Labor Organization (ILO) and implies

that informality is characterized by a high incidence of poverty, inequality and vulnerability

compared to the normal labor deficit standard.

Wan Jie, Huam, Rasli, and Thean Chye (2011) summarized several definitions of the

informal economy based on its causes and taxonomy to better understand the concept and

to reduce the degree of misconceptions. Webb, Bruton, Tihanyi and Ireland (2013) defined

the informal economy as «economic activities that occur outside of formal institutional

boundaries, but which remain within informal institutional boundaries for large segments of

society. Given this definition, informal economy activities are technically illegal yet are not

antisocial in intent (p. 1)».

3. Theoretical approach to the informal economy

Although Frey and Weck (1983) indicated that there is a deficiency of a theoretical structure

to specify the connection between the private sector, the government and the informal

sector to determine the main causes and effects of the informal economy, the later research

foster a framework for the phenomenon. Thus, Wilson (2011) indicated that there are three

ways to view the informal economy: 1) the dualist approach, which considers the informal

sector as an underdeveloped one, where activities are undertaken by low skilled migrants

and the lower skills of the informal workers (2012); 2) the structuralist approach, which

looks for the connections between informal and formal economy as the last one takes

advantage of the first one, following the inner character of the capitalism: looking for more

competitiveness Chen (2012) ; and 3) the legalist approach, that conceives the informal

economy as a product of a mercantilist government: the way for new entrepreneurs to

avoid bureaucratic regulations and succeed in the market. According to Chen (2012), the

cause of this last approach is the «hostile legal system (p. 5)». Finally, Chen (2012) included

the so-called voluntarism approach, according to which informal economy exists because

entrepreneurs openly want to evade taxation and, therefore, they must be forced to

become formal to avoid the inequitable competition.

Galiani and Weinschelbaum (2011) recognized three stylized facts about

informality: 1) small businesses are more probable to operate informally, 2) unqualified

people are more likely to work informally, and 3) workers that are not head of the house are

more likely to work informally in comparison to the head of the house. They then used these

facts to develop a model that clarified the behavior of firms in terms of formal or informal

work, and the corresponding behavior of the labor force and households. Thus, Galiani and

Weinschelbaum (2011) proposed as a policy that «governments should not consider only

labor demand but also labor supply when tackling informality (p. 837)» in addition to the

government needs of enhancing the role played by household in the phenomenon.

McGahan (2012) indicated that management researchers have become more

interested in studying the informality but there are problems related to both the collection

of data and the use of a conceptual definition. Informal activities such as the buses that

pick-up people at regular intervals and in specific places in Nairobi and Los Angeles are

good example for informal economy structures. In fact, for McGahan (2012) the informal

economy is decisive, so he points out:

studying informal activity yields important insights for mainstream theories

of management, pointing to areas of new theorizing on the boundaries of

the firm, diversification, dynamic capabilities, absorptive capacity, property

rights, governance, stakeholder theory, disruptive technology, innovation,

and organizational legitimacy. I argue that research on this sector is not only

an opportunity for management scholars but, also essential to the continued

relevance and vitality of management as a discipline (p. 12).

According to Webb et. al. (2013), most of the research about the informal economy

was centered on phenomenological aspects rather than theoretical ones. Since researchers

in areas such as entrepreneurship and management have become more interested in the

informal economy, a new theoretical framework is needed to analyze the phenomenon

(Webb et. al., 2013): institutional theory, motivation-related theories, and resource allocation

theory are the used ones. In the case of institutional theory, the idea is to analyze how the

institutional setting influence entrepreneurship in the informal economy. The motivationrelated

theories help to understand and structure the reasons why individuals become

informal. And the resource allocation theory shows how strategies are set up to take

advantage of opportunities in a resource-constrained scenario (Webb et. al., 2013).

In the same line, Gibbs, Mahone, and Crump (2014) tried to examine three

theories «culminating in the development of a contextual framework that suggests

appropriate theory selection for informal economy entry decision (p. 33)». These theories

could help policymakers to better understand the phenomenon and increase the theoretical

knowledge about the informal economy. The approach of Gibbs, Mahone, and Crump (2014)

is based on the integration of contextual factors (socio-spatial variations), entry typologies

(necessity-based versus opportunity-driven), external structural factors (structuralist, neoliberal,

and post-structuralist). Factors such as values, customs, culture, cognitive variables,

and social norms are not considered into the analysis and they should be included in future

research. In this line, Achua and Lussier (2014) analyzed the informal business sector in

Cameroon in three subgroups based on surveys: 1) streetwalker entrepreneurs, 2) street

corner entrepreneurs (both driven by necessity) and 3) street owner entrepreneurs (driven

by opportunity). Policies that sustain and encourage informal entrepreneurs at a local

level would be jointly valuable, with more than half of those starting out as need-driven

entrepreneurs progressing to opportunity-driven entrepreneurs form part of the formal

economy (Achua & Lussier, 2014). This shows up the necessity for policy variations to

support entrepreneurs in the informal economy rather than continuing ignoring them as

most governments do.

4. Main causes of informality

Studies on the subject cannot explain the existence of this phenomenon, although there

are several ones that would explain its birth. In general terms, some authors point out

that the main causes are linked to income inequality, poverty, unemployment, economic

growth and economic crises. Other authors consider that causes are more linked to the

excessive regulation introduced by governments and a high tax burden. Within the subject

of excessive regulation, some authors place special emphasis on social and labor regulation

(social security contributions, vacations, etc.). Another reason frequently mentioned is the

so-called social contract or social agreement established between a government and the

country’s population, emphasizing in the concept of tax morale. Institutionalism understood

as the transparency of institutions and governments, as well as the corruption and how laws

and regulations are applied, are added as other causes of informality. Finally, education and

behavioral causes are also considered as a relevant element to understand why informal

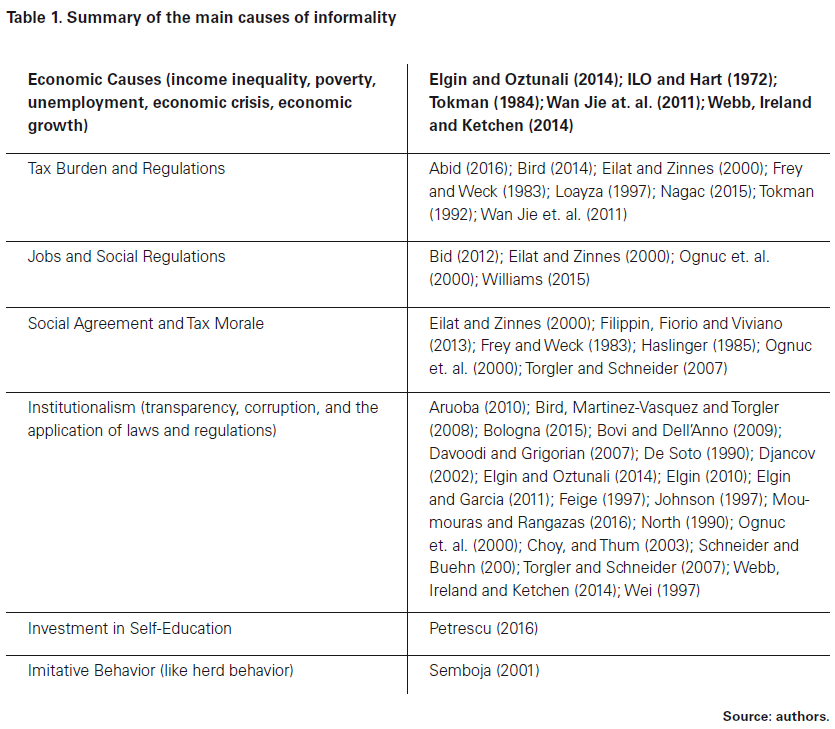

agents stay in informality. The causes of informality are summarized in Table 1:

5. Main consequences of informality

In a similar way that with the causes, the consequences of this phenomenon are numerous.

The effects on economic, social and tax policies are highlighted by informal economy: the

greater the degree of informality, the less effective the social and economic policies become

(ant-inflationary policies, fiscal expansion policies, fight against poverty etc.). Also, lower

level of tax collection is achieved, affected not only by the lower tax compliance per person

but also by the lower tax base. There are also effects on the labor market, specifically in

terms of jobs creation, labor costs, and the skills and productivity of the labor force that

operates in the informal sector, all of which have an impact on the wealth of the population

and the labor regulation. Some authors emphasize the effect of the informal sector on the

market, specifically on the competition between formal and informal companies, considered

disloyal as informal companies don’t comply with regulations, artificially maintaining lower

cost structure. On the other hand, it is recognized that companies operating in the informal

sector tend to be firms with a limited technological capacity and innovation due to, among

other factors, the restriction of funding sources and trained labor, which leads to a reduced

level of productivity and the limitation of value-added. In sum, informal economy ultimately

effects negatively on economic growth of a country. The main consequences of informality

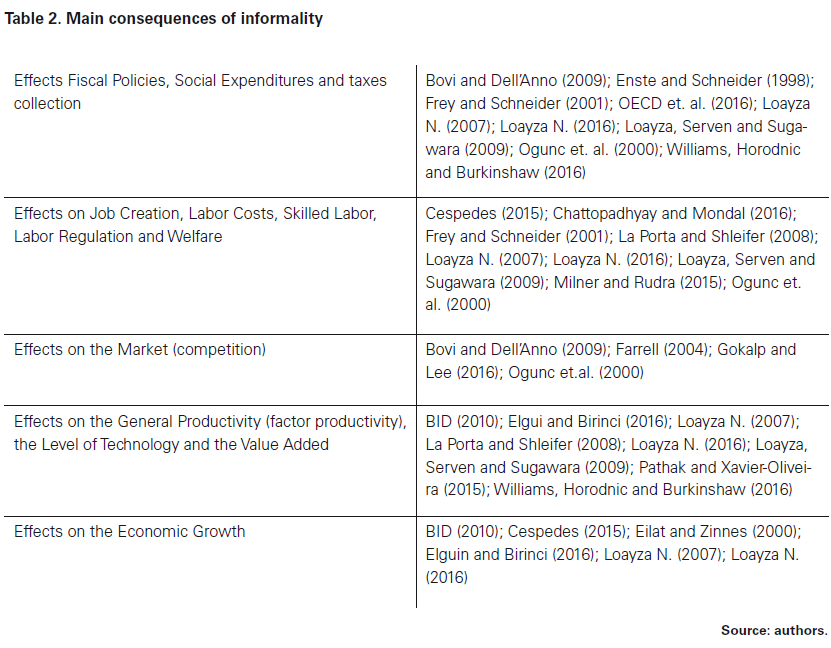

are summarized in Table 2:

6. Formalization reforms and their results

BID (2010) showed the effect of flexible tax regulation and the existence of subsidies on

the informal economy. These issues are further explored by Gómez and Morán (2012), who

analyzed the development of taxation policies in Latin America and showed that spending

in collecting institutions is higher than in developed countries (OECD). Feld and Schneider

(2010) found that, in OECD countries, the level of dissuasion to neutralize informality did not

work well. BID (2012) found that flexibility in tax regulations is better since greater coercion

does not dissuade informality. However, Gómez and Morán (2012) showed that despite the

progress made in reducing the informal economy due to the implementation of policies to

formalize economic agents, yet informality remains with high costs in terms of tax revenue.

Joshi, Prichard and Heady (2014) analyzed the diverse ways in which governments promote

formalization and taxation of informal. There is a belief that taxing informal firms serves

to raise money; however, there is a negative aspect related to the high cost of collecting

and monitoring the process. Besides, taxing informal firms raises issues like coercion and

corrupted behavior from the tax officials. As Joshi, Prichard and Heady (2014) said, the main

reason that leads informal firms to pay taxes is the promotion of a tax culture in a country.

About the mechanisms used by governments to formalize and include informal activities

into taxation, the most used is VAT or indirect taxation (Joshi, Prichard & Heady, 2014).

Other ways to incorporated informal firms in the tax base are enhanced enforcement

and compliance, tax rewards, tax discounts, withholding taxes, and presumptive taxes.

Nevertheless, all these alternatives have shown several problems such as the creation of

complicated tax systems and costly processes of collection and monitoring, as well as

unfairness problems. Even though more research is required, Joshi, Prichard and Heady

(2014) show that there are fewer incentives to promote a formalization and taxation reform

on the side of the politicians and tax officials. Tax evasion is not the main reason for

becoming informal: avoiding regulations, the complexity of the tax system, and the cost of

formalization are probably more important reasons (Joshi, Prichard & Heady, 2014). Many

times, as indicated by the authors (2014), an agent becomes informal due to the lack of

skills and illiteracy (what is called the absence of capacity) and, therefore, is an involuntary

movement. In this case, a formalization program should include not only the adaptation

of the tax system to the characteristics of the informal firms but also topics related to

property rights and dispute resolutions. The interaction between the informal sector and the

government in terms of information (communication about the benefits of being formal),

credibility (government fulfilling its commitment), and coordination (reform including most

of the informal sector) must be addressed when working towards formalization (Joshi,

Prichard & Heady, 2014).

7. How to measure the informal economy

There are two groups of methods: direct and indirect. In the first one, surveys are most

used. In the second one, several methodologies co-exist: the official participation rate of

labor or the employment approach, the income and expenditures approach, the tax fraud

estimation and tax auditing approach, the demand of money or monetary approach, the

transaction approach, the total electricity use, the modified total electricity-based approach,

household electricity use, and the MIMIC and SIMIC models (Andrei, Stefanescu & Oancea,

2010; Eilat, & Zinnes, 2000; Frey & Schneider (2001); Frey & Weck, 1983; Hernandez, 2009;

Ogunc et. al 2000); Smith (1987) used another way to measure the informal economy:

using household purchases from informal vendors. While the advantage of this method is

that buyers are willing to disclose the information, the disadvantage is the differentiation

the buyer has to do between formal and informal vendor.

The lack of interested in the causes and reasons for becoming informal (Frey &

Weck, 1983) complicates the measuring of informal economy. Although there are many

methods to measure the informal economy, Hernandez (2009) recognized that measuring

it is still a problem due to both the lack of a unified definition and the lack of information.

8. Measuring the informal economy in Peru: application of multiple-indicator and multiple-cause models

A multiple-indicator and multiple-cause model (MIMIC) derivative from the structural

equations modeling is used in this research to measure the informal economy. This model

incorporates the causes and consequences of this economic phenomenon into a single

indicator that encompasses all the characteristics of the informal economy. It is important

to remember that, in the case of Peru, a previous measurement was done by Hernandez

(2009), who decided to use the currency demand approach under which «the informal

sector or hidden economy refers to all activity that adds value but is not taxed or registered,

and consequently is beyond official channels of measurement, as mentioned by De Soto

(1986) and Loayza (1996) (p. 86)». Hernandez (2009) indicated that the currency demand

approach (the excessive use of currency) has been criticized due to «the sensitivity of the

results to the assumptions of the model (p. 86)». Hernandez (2009) concluded that the

share of the informal economy on the Peruvian GDP is about 44% to 50%, between 2000

and 2005, which is a result that could be greater if other activities like the illegal ones are

included. In addition, Machado (2014), uses the MIMIC methodology to estimate the size

of the informal economy for the years 1980-2011, his results fluctuate between 30% and

45% of the GDP, his study uses as causes and indicators the variables tax rates, inflation,

GDP per capita, tax evasion rate and net primary enrollment rate. Unlike Torgler & Schneider

(2007) who also use the same methodology, Machado (2014) does not use institutional and

macroeconomic variables to create the size of the informal economy.

In the case of the MIMIC models, Goldberger (1972) pointed out that Structural

Equation Models (SEM) are widely used in behavioral, social, and economic studies to

analyze structural relationships among variables. Some of them may be latent (unobservable)

and SEM cover a wide variety of models and methods for multivariate analysis. Breusch

(2005) indicated that because the informal economy cannot be observed, therefore it

should be estimated. Thus, Breusch (2005) used a MIMIC model to measure the informal

economy. Breusch (2005) recognized that the model has been used in the factor analysis of

psychometrics and, at the beginning, it was used by Zellner in 1970 and Goldberger in 1972

(Breusch, 2005). In the case of the informal economy, Frey and Weck-Hannemann were

the pioneers of using MIMIM models in 1984 (Breusch, 2005). After that, in 1988, Aigner,

Schneider y Ghosh used a refined model called DYMIMIC (because of the use of lagged

variables) (Breusch, 2005). Further, in 1999 Gyles modified again the model to include timeseries

concepts such as unit roots and cointegration (Breusch, 2005). In their research, Giles

and Tedds (2002) presented a Dynamic MIMIC called DYMIMIC (Breusch, 2005). Brambilia

and Cazzavillan (2010) used the MIMIC model to measure informal economy because they

considered that this type of model overcomes the problems of other methods by avoiding

restrictions on the available information and using several variables.

Acock (2013) argued that modeling structural equations offers the ability to use

multiple indicators for each latent variable and isolate it from each measurement of the error,

thus eliminating it for each latent variable assigned. Besides, the power of the prediction

given by the measurement of the error is assumed variable (a random error) and as such has

no explanatory power (Acock, 2013). The results are estimates of the trajectory coefficients

that would generally be larger than if no error was assumed in the predictors, as assumed

with the traditional regression models. The trajectory analysis part of the model is called

structural model and shows the theoretical causal links between the latent variables.

The MIMIC model identifies economic and social phenomena through the

relationships between the variables of their causes and consequences, which is a

necessary aspect but not sufficient. For a MIMIC model to be useful, stronger theoretical

justification is needed. The use of indicators of the model is shown in the section called

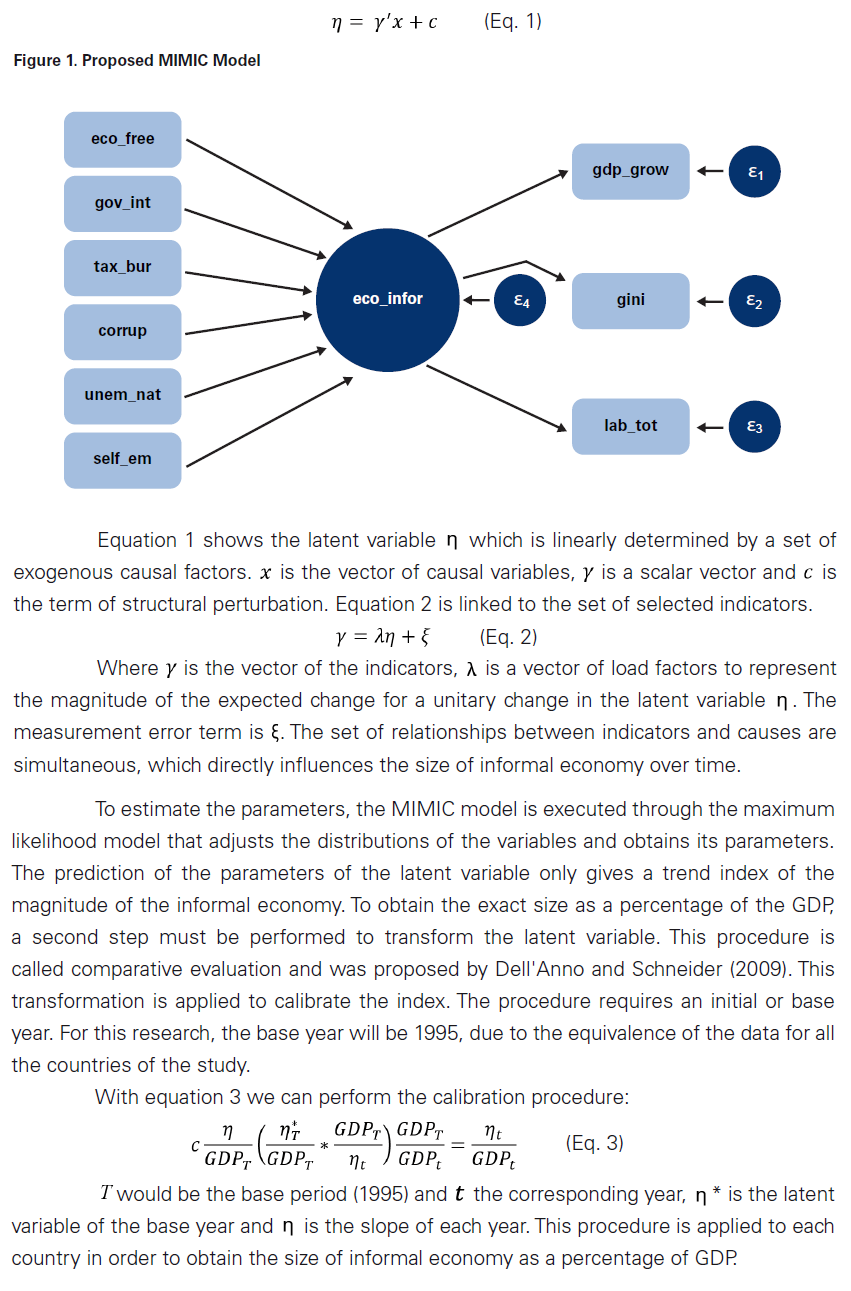

«causes and consequences (indicators)» located above. Figure 1 shows the relationship

between the observed variables (indicators and causes) and the latent variable (size of the

informal economy), which is not directly observed but inferred through observed variables

directly measured. Thus, the MIMIC model is divided into two equations: 1) the structural

model and 2) the measurement model.

To estimate the magnitude of informal economy we use the maximum likelihood

method with a special specification called Satorra-Bentler adjustment. This is done to improve

chi-square statistics of the goodness of fit. In the case of Satorra-Benter, an estimation in

maximum likelihood for non-normal variables can be done because it compensates for the

non-normality of the variables to obtain a robust estimate. The method is described as a

correction of distributions of non-normal variables.

Satorra and Bentler (1994) develop the correction of the value of regular chi-square

for non-normality that requires the estimation of a scale correction factor (c). This reflects

the amount of average kurtosis that distorts the test statistic in the data being analyzed. The

chi-square value of goodness of fit for the model is divided by the scale correction factor to

obtain the so-called Satorra-Bentler chi-square (SB). Normality tests are applied to check the

use of Satorra-Bentler with the variables both separately and as a whole.

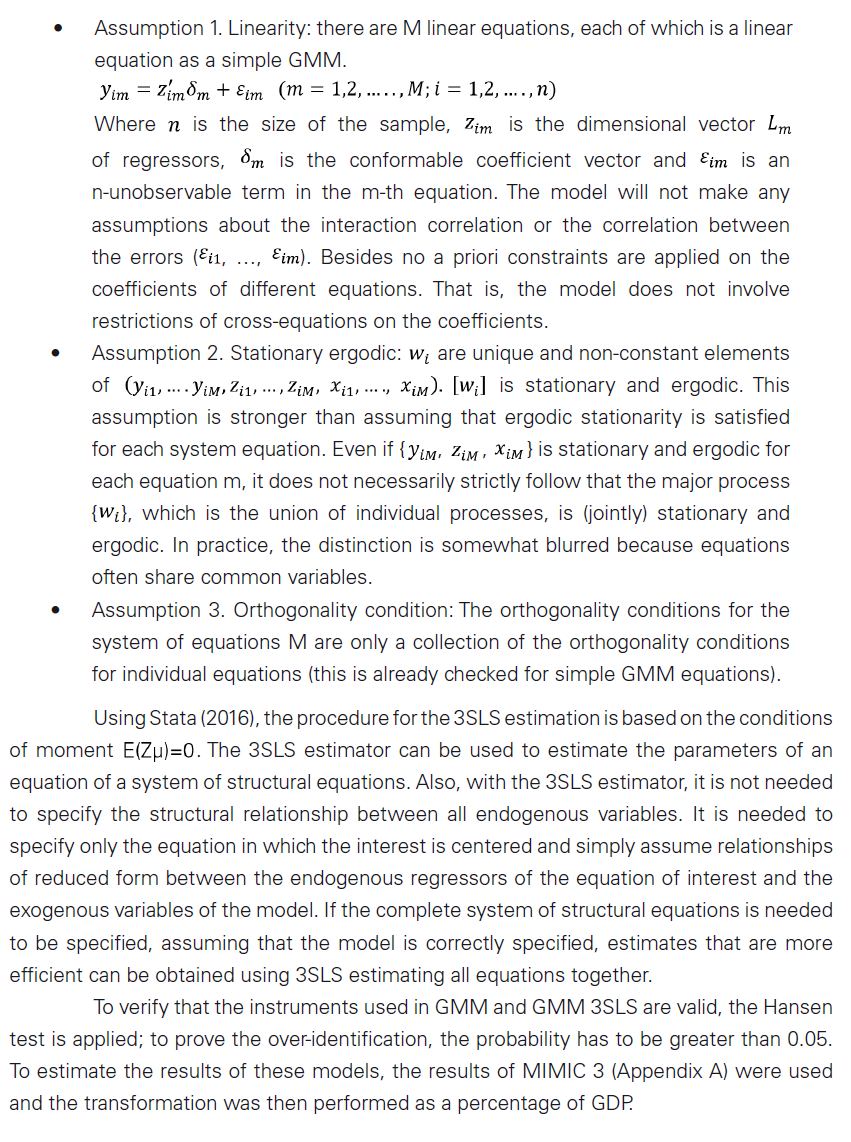

After explaining the detail of MIMIC model estimation, the results are summarized

in Appendix A. The indicators are statistically significant although the same significance is

not found in the case of all the causes. Beyond the significance analysis, the economic

analysis and interpretation of signs become the most important matter. Based on the

premises, MIMIC model 3 is chosen because variables fulfill the economic theory and

satisfy the relations among the variables and the informal economy.

Among the causes we have the economic freedom index that is significant and

related negatively to the latent variable; the government integrity index not significant but

fulfilling the negative relationship with the informal economy; the significant tax burden

index and its positive and proportional relationship –the higher the tax burden, the greater

the informal economy; the significant self-employment rate and its positive relationship

as its growth indicates higher unemployment and therefore a transfer in the informal

employment; tax revenues are not significant but their relation is negative, because the

lower the tax collection, the greater the informal economy; and finally, as self-employment,

unemployment is also directly proportional to informal economy, with greater presence of

the latent variable.

Indicators are affected by the dimension of the informal economy. Thus, the

Gini coefficient is significant, and it shows a positive relationship with informal economy

(the greater the inequality, the greater the latent variable); the labor freedom index is

not significant, but its relationship is negative as a lower labor freedom means a higher

informal employment; GDP growth is significant, but with a positive relationship. Hassan

and Schneider (2016) took the GDP variable as a reference and associated it with -1. This

modification is called «reduction ad absurdum» which is based on the negative relationship

of informal economy with GDP growth that is fulfilled for developed countries (OECD).

However, this research found that this variable has a positive relationship in Latin American

countries.

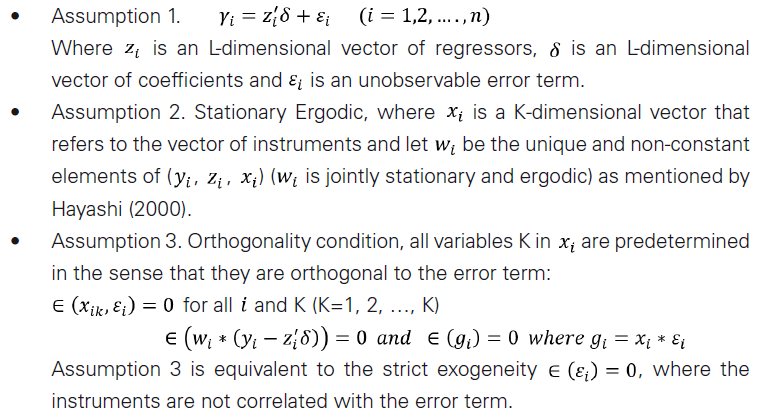

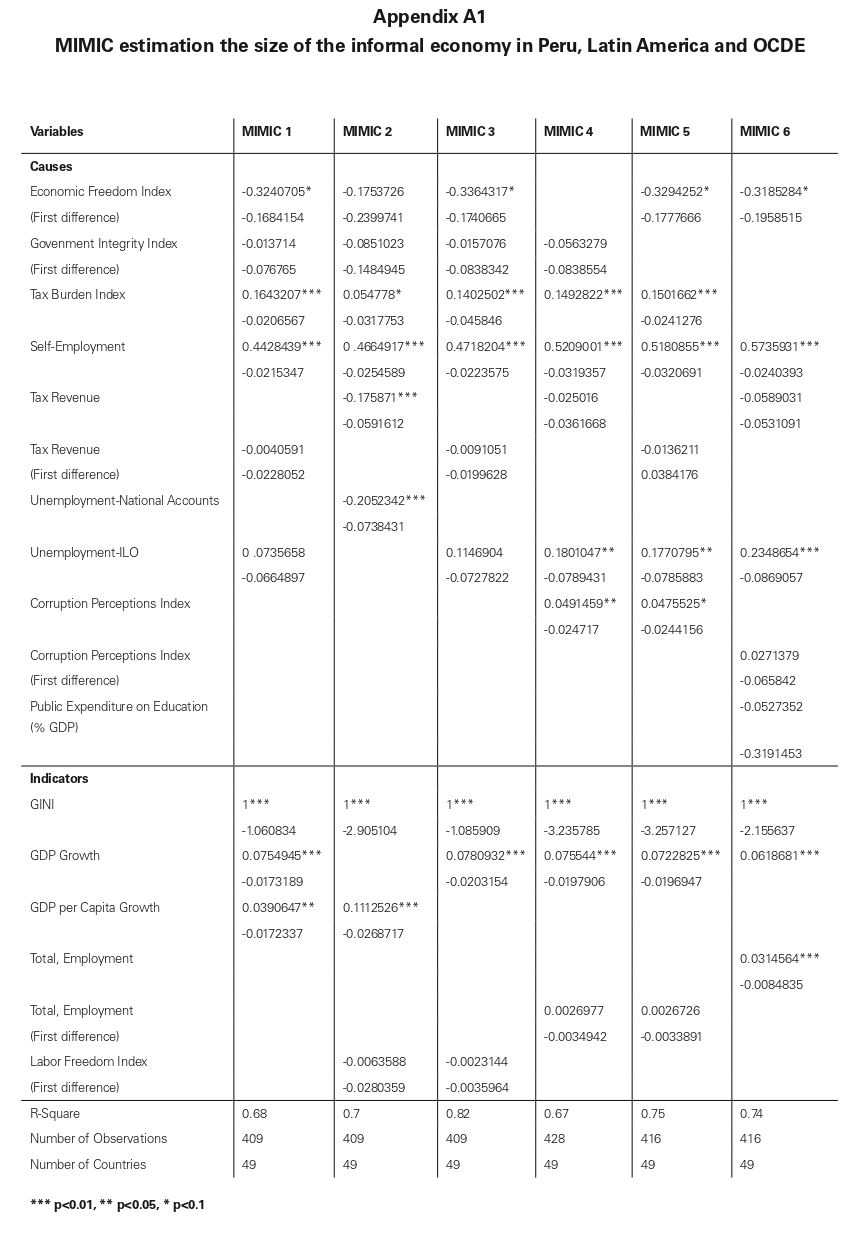

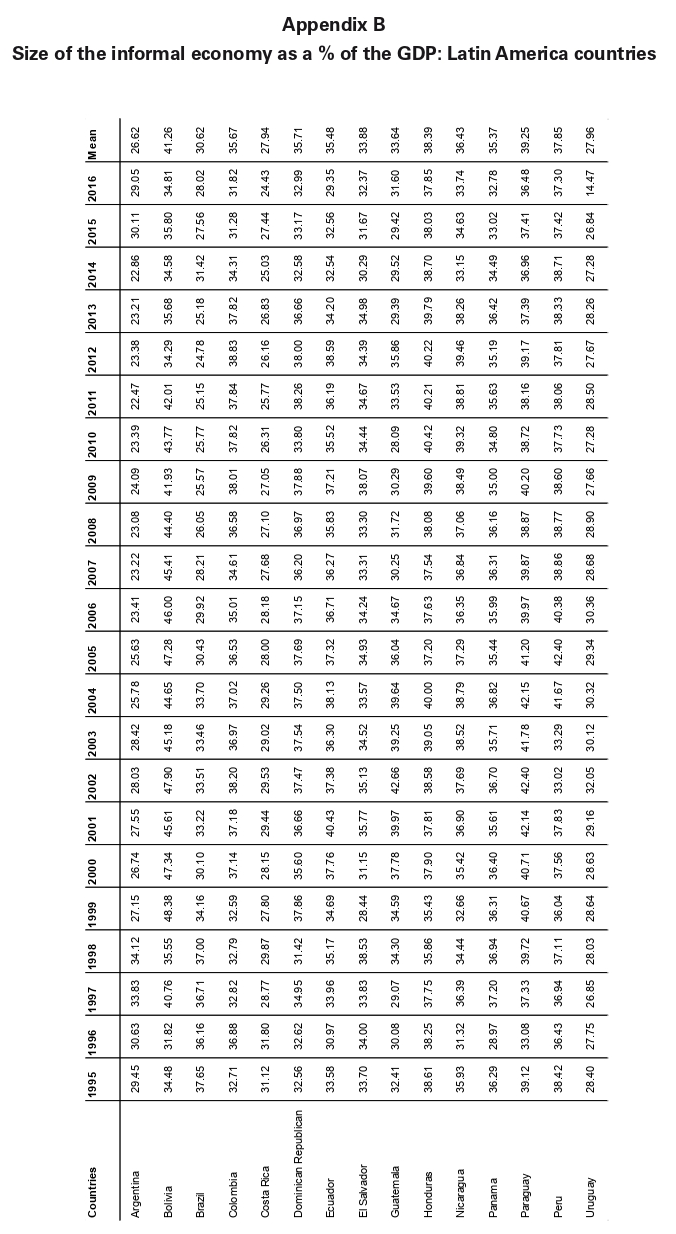

We apply the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) to observe the impact of

informal economy on economic growth and tax collection, while identifying the relationship

between the dependent and the instrumental variables. The method is appropriate

because informal economy has many causes and consequences that relate to each other.

Hayashi (2000) indicated that the most critical assumption made for the OLS model is the

orthogonality between the error term and the regressors: without it, the OLS estimator

is not reliable. Since in many important applications the orthogonality condition is not

satisfied, it is essential to be able to deal with the endogenous regressors (Hayashi, 2000).

Guillermo Boitano & Deyvi Franco Abanto140

The estimation method called the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), which includes

OLS as a special case, provides a solution (Hayashi, 2000). In the frame of this research, the

assumption of strict exogeneity does not apply for the model presented because informal

economy affects many other variables outside the model and requires instrumental variables

pertinent to the correlated (endogenous) variables with the error term. To comply with the

GMM assumptions, the model must be linear in compliance with the model proposed by

Hayashi (2000).

Torgler and Schneider (2007) and MEF (2016) used the Generalized Method of

Two-stage Moments (G2SM) due to the high endogeneity presented by the variables that

cause informality. This method corrects problems of endogeneity and includes instrumental

variables accomplishing a better explanation of the variables that have a high correlation.

Hayashi (2000) deals with this problem estimating more than one equation jointly

by GMM. After using GMM in a single equation it is necessary to follow a few more steps to

arrive at a multiple equation system. This is because the multiple equations GMM estimator

can be expressed as a simple equation GMM estimator by properly specifying the matrices

and vectors comprising the simple equation GMM formula. This being the case, it can be

developed the GMM large sample theory of multiple equations almost off the platform.

Hayashi (2000) considered that the gain of dominating the GMM multiple

equations is considerable. Under conditional homoscedasticity, it is reduced to the efficient

estimator of the instrumental variable of complete information, which in turn is reduced

to the three-stage least squares (3SLS) if the set of instrumental variables is common to

all equations. If it is further assumed that all regressors are predetermined, then 3SLS

is reduced to seemingly unrelated regressions, which in turn is reduced to multivariate

regression when all equations have the same regressors.

9. Results, conclusions and recommendations

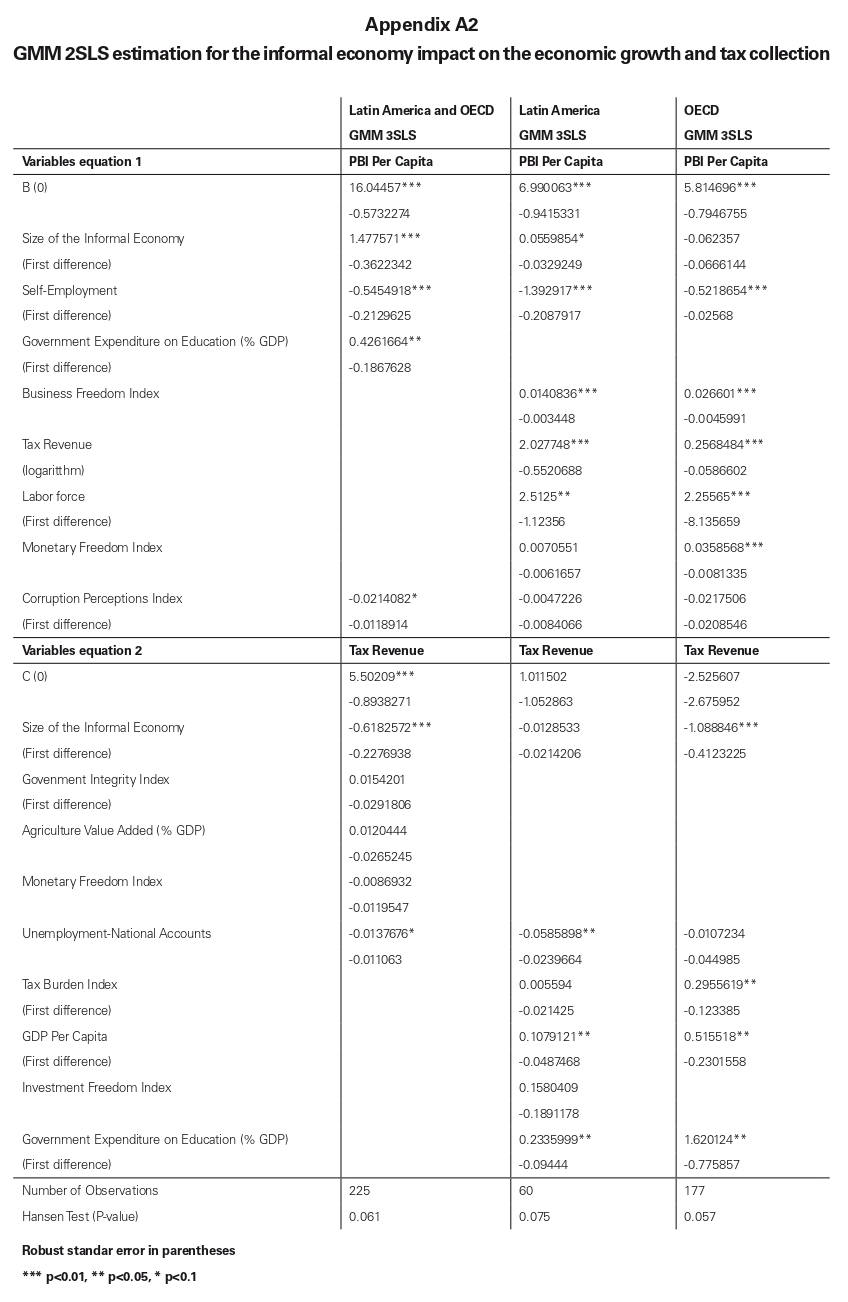

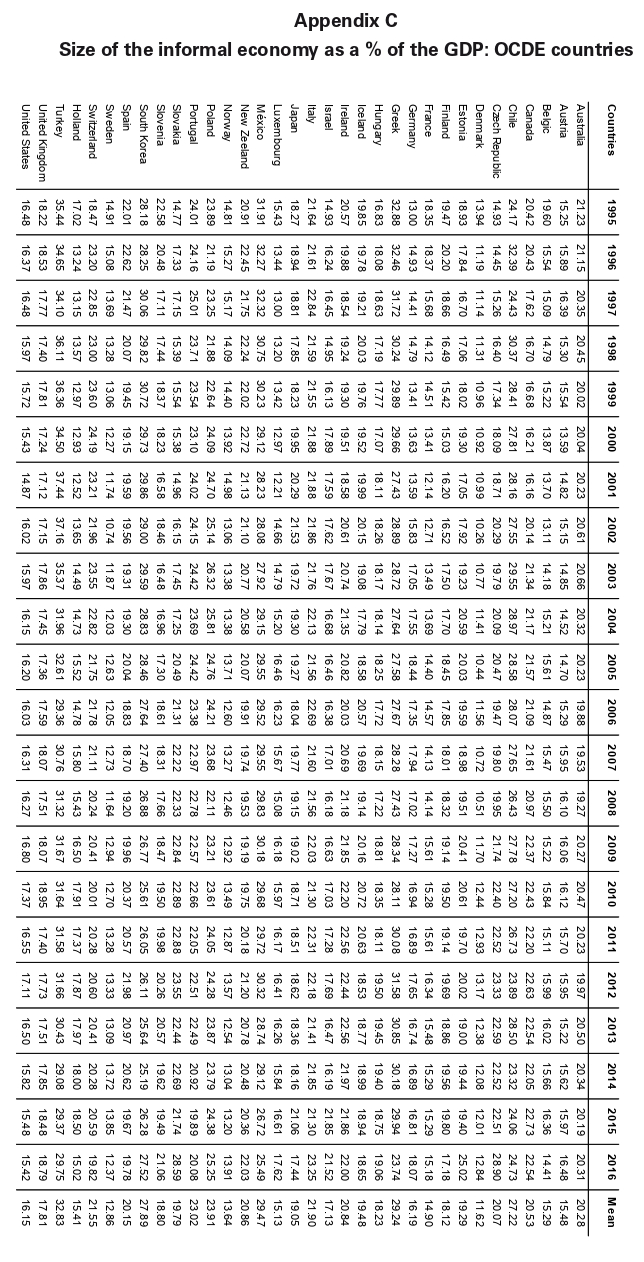

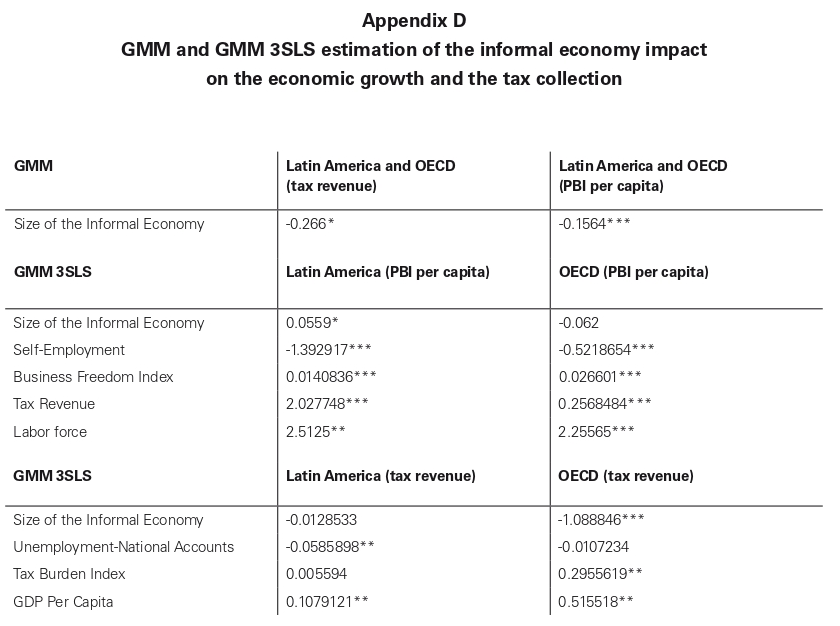

The final model to estimate the dimension for informal economy was the MIMIC 3 showed

in Appendix A, and the results are found in Appendix B and Appendix C. The same analysis

was performed by Adame and Tuesta (2017) to study the impact of informal economy on

both institutional variables (corruption control, government efficiency, tax collection and

state effectiveness) and macroeconomic variables (self-employment, GINI, unemployment

rate and GDP growth). More results are shown in Appendix D.

According to the present research, the estimated average size of informal

economy as a percentage of the GDP for Latin America is 34% while, in the case of the

OCDE countries, it is 19.83%, a little bit less than a half of the Latin American average.

The difference between those groups of countries is due to institutional efficiencies and

the economic development of each country. The country with the biggest informality in

America Latina is Peru, with 37.4% of the GDP for 2016; in the case of the OCDE countries,

it is Turkey with 29.75% for the same period time. Moreover, the Latin American country

with less informality is Uruguay with 14.47% while in the OCDE countries is Denmark with

12.84%, both for 2016.

In Hassan and Schneider’s results for 2013, the dimension of the informal economy

for Peru (60.9%) is approximately less than twice the estimated in the present research.

The 17.3% estimation made by the INEI (2016) shows a figure which is approximately onethird

of the number gotten by Schneider. Finally, this research shows proportion which

is a bit less than the double of the INEI’s estimation, although the trend is the same in

both cases (INEI and the present research). The countries with larger informal economy

according to Hassan and Schneider (2016) are Bolivia (66.04%) and Honduras (72.41%)

followed by Mexico (31.19%) and Greece (39.39%). A possible explanation for the big

number in Hassan and Schneider’s results is the fact that they included in their model the

demand of money as an indicator with the premise that an excess of demand over supply

is due to informality, but it may be also explained by the existence of illicit activities that

demand cash.

The results indicate that for Peru, Latin America and OECD countries, the tax

collection has been negatively affected due to the dimension of the informal economy. In

the case of Latin America, the policies applied to reduce the informal sector have resulted

in an average reduction from 34% to 31.4% between 1995 and 2016. In contrast, for OECD

countries, it remained at 20% throughout the years of study. In both cases, it can be

inferred that policies to reduce informal economy such as reducing taxes and eliminating

economic barriers to become formal have not been successful. These results opened new

lines of research to find out the motivations to stay in the informal economy and to question

the insertion into formality.

For Latin America, De Soto (1980) statements on the informality as a source of

entrepreneurship are confirmed since the GMM 3SLS estimation shows a positive impact

of the informal economy on the economic growth. The opposite happens in the case of

OCED countries, where a negative effect could be found. For both Latin America and OCED

countries, the informal economy harms the amount of collected taxes.

Although the informal economy is present in all countries, it is greater in the

developing ones and the fixed effect in each country is persistent. Thus, solutions must

not be the same for all countries and must consider the differences in cultures and

idiosyncrasy. Policies such as barriers reductions for formalization or tax reductions are not

solutions by themselves in isolation. The institutional framework (including the government)

is an important factor to increase or decrease the informal economy. If institutions are not

interested in being more efficient, transparent and committed to people’s welfare, it is

less probable that the informal economy could be reduced. The institutional issue must be

addressed definitively considering the elimination of corruption at all levels of the economy.

In the same line, Laws and regulations must not only be clear to prevent unequal application

but also must be fulfilled regardless of who the subject is. Moreover, the self-employment

and unemployment are directly related to informal employment, which absorbs what formal

employment could not recruit. The Gini coefficient is an important indicator because a

country with higher inequality would probably have a bigger informal economy.

The controversy about MIMIC models is well-known. Although to better improve

the goodness of fit, after getting the slope of the informal economy using the MIMIC,

the adjustment procedure could be calibrated considering the INEI’s first study about the

informal economy in Peru. Another criticism of the MIMIC model is the fact that illicit

activities cannot be completely separated from informal activities because the former

groups hide their income. Finally, the model requires a great amount of data and, therefore,

it is not possible to analyze only one country.

Some conclusions can be obtained after all the research review. First of all, the

need to reinforce theoretical framework in order to understand the informal economy as

agents’ behavior. Secondly, a unique solution (a recipe) is not feasible: we need to adapt the

possible solutions to the specific causes of informal economy in each country. Thirdly, all

agents (government and institutions, formal sector, informal sector and individual agents)

must be considered because each particular behavior exerts an effect on the dimension of

the informal economy. Fourthly, facts such as confidence in the government and politicians,

transparency and efficiency in the government’s expenditures, elimination of corruption,

increasing the perceived social welfare and education are probably more important and

effective variables to take into account to reduce informality than tax reduction programs. A

complete set of formalization policies must be considered besides creating and maintaining

economic growth. Lastly, it should be understood that the final result will be seen in the

long run.

From the point of view of public management, trying to solve the problem does

not only mean taking the perspective of the rational economic actor but combining it with

that of the social actor: whether an agent’s participation in the informal sector is due to

a low moral tax measured or by what is called the civil morality (Williams, Horodnic, &

Burkinshaw, 2016). In this context, the way to solve the informality problem would be to

incentivize the tax morality, independently of the other policy measures that the state can

adopt. But for this to happen, governments must increase, promote and communicate

(not only with rules but with their actions) the «state morality» as an institution (Williams,

Horodnic, & Burkinshaw, 2016, p. 368). This state morality has to do with the moral

responsibilities of the state. For the application of this idea, the thought of Williams (1923)

must be followed while defining a conception of the state:

A community of people socially united; secondly, a piece of political machinery

termed a government, and administered by a corps of officials termed a magistracy;

and thirdly, a body of rules or maxims, written or unwritten, determining the scope

of this public authority and the manner of its exercise. (p. 22).

And one way to increase both the civic morality (which includes tax morality) and

the state morality is through education.

It is also necessary to understand that informal agents are not criminals and that

informality should be analyzed considering two basic things that sometimes go unnoticed:

on the one hand, informality in Peru has a lot to do with social and economic inequalities;

and on the other hand, it is a mechanism of capitalist development of an enterprise that, if

well managed, could positively stimulate economic growth. From this standpoint of view,

government’s policies must-see at informals as entrepreneurs who requiered in most cases

education, social protection, financing, technology and improvement of skills to develop

their enterprises (Lupi, 2018). And that's the place where management science could help

the informal entities to successfully achieve their potential.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Bibliografía

Abid, M.

(2016)-Size and implication of the informal

economy in African countries: Evidence

from a structural model. International

Economic Journal, 30(4), 571-598. DOI:

10.1080/10168737.2016.1204342

Achua, C., & Lussier, R.

(2014)-Entrepreneurial drive and the informal

economy in Cameroon. Journal of

Developmental Entrepreneurship, 19(4).

Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1142/

S1084946714500241

Acock, A.

Structural equation modeling. Discovering

structural equation Modeling Using Stata,

115-152. Washington: STATA Press.

Adame, V., & Tuesta, D.

(2007)-El laberinto de la economía informal:

estrategias de medición e impactos. BBVA

Research Working Paper 17/17.

Allingham, M., & Sandmo, A.

(1972)-Income tax evasions: A theoretical

analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1(3),

323-338.

Andrei, Tudorel, Stefanescu, Daniela & Oancea, Bogdan

(2010)-Quantitative methods for evaluating the

informal economy. Theoretical and Applied

Economics, 17(7), 15-24.

Aruoba, S.B.

(2010)-The Informal sector, government policy

and institutions. Society for Economic

Dynamics.

BID.

(2010)-La era de la productividad. Cómo

transformar las economías desde sus

cimientos, 1-29. Washington: Fondo de

Cultura Económica.

BID.

(2012)-Recaudar no basta: Los impuestos como

instrumento de desarrollo. Washington:

Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Bird, R., Martinez-Vasquez, J. & Torgler, B.

(2008)-Tax effort in developing countries and

high income countries: The impact of

corruption, Voice Accountability. Economic

Analysis and Policy, 38(1), 55-71.

Bird, R., Martinez-Vasquez, J. & Torgler, B.

(2014)-Societal institutions and tax effort. Annals

of Economics and Finance, 15(1), 301-351.

Bologna, J.

(2015)-The effect of informal employment and

corruption on income levels in Brazil.

Journal of Comparative Economics, 44(3),

657-695.

Bovi, M., & Dell’Anno, R.

(2009)-The changing nature of the OECD

shadow economy. Journal of Evolutionary

Economics. Springer 2019.

Brambila, M.J, & Cazzavillan, G.

(2010)-Modeling the informal economy in Mexico.

A structural equation approach. The Journal

of Developing Areas, 44(1), 345-365.

Breusch, T.

(2005)-The Canadian underground economy: An

examination of Giles and Tedds. Canadian

Tax Journal. 53(2), 367-391.

Breusch, T.

Estimating the underground economy

using MIMIC models. EconWPA, 1-35.

Bruton, G.D., Ireland, R.D. &

Ketchen Jr., D.J.

(2005)-Toward a research agenda on the informal

economy. Academy of Management

Perspectives, 26(3), 1-11. DOI: 10.5465/

amp.2012.0079

Buehn, A., Dell’Anno, R. & Schneider, F.

(2012)-Fiscal illusion and the shadow economy:

Two sides of the same coin?. Munich

Personal RePEc Archive.

CEPLAN

(2016)-Economía informal en Perú: Situación

actual y perspectivas. Lima.

Céspedes, R. N.

(2015a)-Crecer no es Suficiente para Reducir la

Informalidad. Lima: BCRP.

Chattopadhyay, S., & Mondal,R.

(2016)-Investment and growth in a developing

economy with vast informal sector. The

Journal of Developing Areas, 50(4), 113-

132.

Chen, A.M.

(2012)-La economía informal: definiciones, teorías y políticas. WIEGO.

Choy, J.P., & Thum, M.

(2003)-Corruption and the shadow economy. Dresden discussion paper in economics.

Colin, C.W.

(2006)-Explaining the hidden enterprise

culture. The hidden enterprise culture:

Entrepreneurship in the underground

economy, 92-97. Massachusetts: Edward

Elgar Pub.

Colin, W.C., & Nadin, S.

(2011)-Theorizing the hidden enterprise

culture: the nature of entrepreneurship

in the shadow economy. Journal

Entrepreneurship and Small Business,

14(3), 334-348.

Darbi, W., & Knott, P.

(2016)-Strategizing practices in an informal

economy setting: A case of strategic

networking. European Management

Journal, 34(1), 400-413.

Davoodi, H., & Grigorian, D.

(2007)-Tax potencial vs. tax effort: A cross-country

analysis of Armenia Stubbornly Low Tax

collection. IMF Working Paper.

De Soto, H.

(1986)-El otro sendero. Lima: Instituto Libertad y Democracia.

Dell'Anno, R., & Schneider, F.

(2009)-A complex approach to estimate the

shadow economy: The structural equation

modeling. In M. Faggini and T. Lux (Eds).

Coping with the complexity of economics,

111-130. Verlag, Italy: Springer.

Eilat, Y., & Zinnes, C.

(2000)-The evolution of the shadow economy in

transitions countries: Consequences for

economic growth and donor assistance.

Harvard Institute for International

Development. CAER II Discussion Paper

83, 11-69. Retrieved from: http://citeseerx.

ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid

=57CDE74EDE5653D9626C731EA5FEA

0C4?doi=10.1.1.470.2018&rep=rep1&ty

pe=pdf

Elgin, C.

(2010)-Political turnover, taxes and the shadow

economy. Department of Economics at

Bogazici University, 1-51. Retrieved from:

http://www.econ.boun.edu.tr/public_html/

RePEc/pdf/201008.pdf

Elgin, C., & Garcia, M.

(2011)-Public trust, taxes and the informal sector.

Journal Review of Social, Economic and

Administrative Studies, 26(1), 27-44.

Retrieved from: http://www.acarindex.com/

dosyalar/makale/acarindex-1423873575.pdf

Elgin, C., & Oztunali, O.

(2012)-Shadow economies around the World:

Model based estimates. Department of

Economics at Bogazici University Working

Papers 2012/05, 1-48. Retrieved from:

http://www.econ.boun.edu.tr/public_html/

RePEc/pdf/201205.pdf

Elgin, C., & Oztunali, O.

(2014)-Institutions, informal economy, and

economic development. Emerging Markets

Finance & Trade, 50(4), 145-162.

Elgin, C., & Schneider, F.

(2016)-Shadow economies in OECD countries:

DGE vs. MIMIC approaches. Journal

Review of Social, Economic and

Administrative Studies, 30(1), 51-75.

Enste, D., & Schneider, F.

(1998)-Increasing shadow economies all over the

World - Fiction or reality? Institute for the

Study of Labor Discusion Paper 26, 1-65.

Retrieved from: http://ftp.iza.org/dp26.pdf

Enste, D.

(2015)-The shadow economy in industrial

countries. Institute for the Study of Labor

Discusion Paper 2(127), 1-11. Retrieved

from: https://wol.iza.org/uploads/

articles/457/pdfs/shadow-economy-inindustrial-

countries.pdf?v=1

Farrell, D.

(2004)-The Hidden dangers of the informal

economy. McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved

from: https://www.mckinsey.com/featuredinsights/

employment-and-growth/thehidden-

dangers-of-the-informal-economy

Feige, E. L.

(1997)-Underground activity and institutional

change: productive, protective and

predatory behavior in transition economies.

In J.M. Nelson, C. Tilly, and L. Walker

(Eds.). Transforming post-comunist political

economies, 21-34. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press.

Feld, L. P., & Schneider, F.

(2010)-Survey on the shadow economy and

undeclared earnings in OECD countries.

German Economic Review, 11(2), 109-149.

Filippin, A., Fiorio, C., & Viviano, E.

(2013)-The effect of tax enforcement on tax

moral. Bank of Italy, Economic Research

and International Relations Area Economic

Working Paper 937, 1-29.

Frey, B., & Schneider F.

(2001)-Informal and underground economics.

In N.J. Semelser and P.B. Baltes (Eds.).

International Encyclopedia of the Social

and Behavioral Sciences (1st ed.), 7441-

7446.

Frey, B., & Weck, H.

(1983)-Estimating the Shadow Economy: A naive

Approach. Oxford Economic Papers, 35(1),

23-44.

Friedman, E., Johnson, E.,

Kaufmann, D., &

Zoido-Lobaton, P.

(2000)-Dodging the Grabbing Hand: The

Determinants of Unofficial Activities in 69

Countries. Journal of Public Economics,

76(3), 459-493.

Galiani, S., & Weinschelbaum,F.

(2011)-Modeling Informality Formally: Households

and Firms. Economic Inquiry, 50(3), 821-

838.

Gibbs, S.R., Mahone Jr., C.E., & Crump, M.E.S.

(2014)-A Framework for informal economy entry:

Socio-spatial, necessity-opportunity, and

structural-based factors. In M. Bressler

(ed.). Academy of Entrepreneurship

Journal 20(2), 33-58. Weavervile, USA:

Jordan Whitney Enterprises Inc.

Goel, R.K., & Nelson, M.A.

(2016)-Shining a light on the shadows: Identifying

robust determinants of the Shadow

Economy. Economic Modelling, 58(1),

351-364.

Gokalp, O., & Lee, S.H.P.

(2016)-Competition and corporate tax evasion:

An institution-based view. Journal of World

Business, 52(2), 258-269.

Goldberger, A.S.

(1972)-Structural equation methods in the social

sciences. Econometrica, 40(6), 979-1001.

Gómez, S.J., & Moran, D.

(2012)-Informalidad y tributación en América

Latina: Explorando los nexps para mejorar

la equidad. Serie Macroeconomia el

Desarrollo 124. Santiago: CEPAL.

Gylys, P.

(2005)-Economy, anti-economy, underground

economy: Conceptual and terminological

problems. Ekonomika, 72. Vilnius University

Publishing House.

Hart, K.

(1973)-Informal income opportunities and urban

employment in Ghana. Journal of Modern

African Studies, 11(1).

Haslinger, F.

(1985)-Reciprocity, loyalty, and the growth of the

underground-economy: A theoretical note.

European Journal of Political Economy,

1(3), 309-323.

Hassan, M., & Schneider, F.

(2016)-Size and development of the shadow

economies of 157 countries Worldwide:

Updated and new measures from 1999 to

2013. Journal of Global Economics, 4(3),

1-14.

Hayashi, F.

(2000)-Multiple-equation GMM. En F. Hayashi (Ed.). Econometrics, 258-320.

Hayashi, F.

(2000)-Single-equation GMM. En F. Hayashi (Ed.). Econometrics, 198-202.

Hernandez A.M.

(2009)-Estimating the size of the informal

economy in Peru: A currency demand

approach. Revista de Ciencias

Empresariales y Económicas.

INEI

(2014)-Produción y empleo informal en el Perú:

cuenta satélite de la economía informal

2007-2012. Lima: INEI.

INEI

(2016)-Evolución de la pobreza monetaria 2009- 2015. Lima: INEI.

INEI

(2016)-Producción y empleo informal en el Perú:

cuenta satélite de la economía informal

2007-2015. Lima: INEI.

INEI

(2017)-http://www.inei.gob.pe/. Retrieved from:

https://www.inei.gob.pe/estadisticas/

indice-tematico/education/

Joshi, Anuradha; Prichard, Wilson & Heady, Christopher

(2014)-Taxing the informal economy: The current

state of knowledge and agendas for future

research. The Journal of Development

Studies, 50(10), 1325-1347.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A. & Mastruzzi, M.

(2014)-Governance matters III: Governance

indicators for 1996-2014. World Bank.

La Porta, R., & Shleifer. A.

(2008)-The economic consequences of legal

origins. Journal of Economic Literature,

46(2), 285-332.

Loayza, N.

(1997)-The economics of the informal sector: A

simple model and some empirical evidence

from Latin America. Lima: The World Bank.

Loayza, N.

(2007)-The causes and consequences of informality in Peru. BCRP.

Loayza, N.

(2016)-Informality in the process of development

and growth. World Bank Group.

Loayza, N. V., Serven, L., & Sugawara, N.

(2009)-Informality in Latin America and the Caribbean. The World Bank.

Lupi, A.

(2018)-Main sectoral approaches of policies

designed to tackle the informal economy.

Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/

capacity4dev/rnsf-mit/wiki/43-mainsectoral-

approaches-policies-designedtackle-

informal-economy

Machado, R.

(2014)-La economía informal en el Perú: magnitud

y determinantes (1980-2011). Apuntes,

41(74), 197-233. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la

Universidad del Pacífico.

Mathias, B., Lux, S., Crook, R.,

Autry, C., & Zaretzki, R.

(2015)-Competing against the unknown: The

impact of enabling and constraining

institutions on the informal economy.

Journal of Business Ethics, 127(2), 241-

264.

McGahan, A.

(2012)-Challenges of the informal economy for

the field of management. Academy of

Management Perspectives, 26(3), 12-21.

MEF.

(2016)-Marco macroeconomico multianual 2017-

2019 Revisado. LIMA: MEF.

Milner, H., & Rudra, N.

(2015)-Globalization and the political benefits

of the informal economy. International

Studies Review, 17(4), 664-669.

Mukherjee, D.

(2016)-Informal economy in emerging economies:

not a substitute but a complement!

International Journal of Business and

Economic Development, 4(3).

Nagac, K.

(2015)-Tax system and informal economy: a

cross-country analysis. Applied Economics,

47(17), 1775-1787.

North, D. C.

(1990)-Institutions, institutional change and

economic performance. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

OCDE

(2002)-Measuring the non-observed economy: A

handbook. OCDE. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OCDE, CEPAL, CIAT, & BID

(2016)-Estadisticas tributarias en América Latina y

el Caribe 2016. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OCDE, ECLAC, CIAT, & IDB

(2016)-Revenue statistics in Latin America

and the Caribbean 2016. Paris : OECD.

Retrieved from: http://www.cepal.org/

es/comunicados/america-latina-caribeingresos-

tributarios-aumentan-ligeramentepero-

aun-se-mantienen

Ogunc, Fethi, Yilmaz & Gokhan

(2000)Estimating the underground economy in

Turkey. The Central Bank of the Republic of

Turkey Research Department.

OIT

(1972)-Employment, incomes and equality:

A strategy for increasing productive

employment in Kenya. Ginebra: OIT.

Pathak, S., & Xavier-Oliveira, E.

(2015)-Technology use and availability in

entrepreneurship: informal economy as

moderator of institutions in emerging

economies. The Journal of Technology

Transfer, 41(3), 506-529.

Petrescu, I.

(2016)-The Effects of economic sanctions on the

informal economy. Management Dynamics

in the Knowledge Economy, 4(14), 623-

648.

Sassen, S.

(1994)-The Informal economy: Between new

developments and old regulations. The Yale

Law Journal, 103(8), 2289-2304. Retrieved

from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/797048

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P.

(1994)-Corrections to test statistic and standar

errors in covariance structure analysis.

SAGE Publications Inc.

Schneider, F., & Buehn, A.

(2009)-Shadow economies and corruption all

over the World: Revised estimates for

120 Countries. Economics: The Open-

Access, 2(1), 1-53. Retrieved from: http://

www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/

journalarticles/2007-9

Schneider, F., & Colin, W.

(2013)-The shadow economy. London: The

Institute of Economic Affairs.

Semboja, J.

(2001)-Why people pay taxes: The case of the

development levy in Tanzania. Tanzania.

World Development, 29(12), 2059-2074.

Smith, D. J.

(1987)-Measuring the informal economy.

The Annals of the American Academy

of Political and Social Science,

493(1), 83-99. DOI: https://doi.

org/10.1177/0002716287493001007

Stata

(2016)-http://www.stata.com/. Retrieved from:

http://www.stata.com/: http://www.stata.

com/manuals13/rgmm.pdf

Tanzi, V.

(1982)-Fiscal disequilibrium in developing

countries. World Development, Vol. 10, No.

12, 1069-1082. Retrieved from: https://doi.

org/10.1016/0305-750X(82)90019-5

Tokman, V.

(1984)-Wages and employment in international

recessions: Recent Latin American

experience. The Helen Kellogg Institute

for International Studies. Working Paper

11. Retrieved from: https://kellogg.

nd.edu/sites/default/files/old_files/

documents/011_0.pdf

Tokman, V.

(1992)-Beyond regulation: The informal economy

in Latin America (1st ed.). Boulder, CO:

Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Torgler, B., & Schneider, F.

(2007)-The impact of tax morale and institutional

quality on the shadow economy. The

Institute for the Study of Labor Discussion

Paper 254, 1-46.

Voicu, Cristina

(2012)-Economics and «underground» economy

theory. Theoretical and Applied Economics,

Vol. XIX(7), 71-84

Wan Jie, S., Huam, T., Rasli, A.,

& Thean Chye, L.

(2011)-Underground economy: Definitions and

causes. Business and Management

Review, 1(2), 14-24.

Webb, J.W., Bruton, G.D., Tihanyi, L., & Ireland, R.D.

(2013)-Research on entrepreneurship in the

informal economy: Framing a research

agenda. Journal of Business Venturing,

1(17). DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.003

Webb, J.; Ireland, D. & Ketchen, D.

(2014)-Toward a greater understanding of

entrepreneurship and strategy in

the informal economy. Strategic

Entrepreneurship Journal, 8(1), 1-15.

Wei, S.

(1997)-Why is corruption so much more taxing

than tax? Arbitrariness kills. The National

Bureau of Economic Research. WP 6255,

1-25. Retrieved from: https://www.nber.

org/papers/w6255

Welter, F., Smallbone, D., & Pobol, A.

(2015)-Entrepreneurial activity in the

informal economy: a missing piece

of the entrepreneurship jigsaw

puzzle. Entrepreneurship & Regional

Development, 27(1), 292-306.

Williams, B.

(1923)-State morality in international relations.

The American Political Science Review,

17(1), 17-33. Retrieved from: https://www.

jstor.org/stable/pdf/1943790.pdf

Williams, C.

(2015)-Explaining the informal economy: An

exploratory evaluation of competing

perspectives. Industrial Relations, 70(4),

741-765.

Williams, C.

(2015)-Tackling entrepreneurship in the informal

sector: an overview of the policy

options. Journal of Developmental

Entrepreneurship, 20(1).

Williams, C., Horodnic, I., &

Burkinshaw, L.

(2016)-Evaluating competing public policy

approaches towards the informal economy.

International Journal of Public, 29(4).

Wilson, D. Tamar

(2011)-economy. Urban Anthropology and Studies

of Cultural Systems and World Economic,

40(3/4), 205-221.

Fecha de recepción: 03 de octubre de 2018

Fecha de aceptación: 15 de noviembre de 2018

|

|

|

|